In the absence of accountability for the massacre in Bijeljina, Rolling Stone partnered with the Starling Lab to help archive and authenticate key records.

We are providing access to photos, videos, social media posts, and documents from our reporting.

The Starling Lab is a research center co-founded by Stanford University and USC Shoah Foundation to pursue innovation and education in data integrity.

The Photograph01

Revisit one of the most iconic images from the Bosnian War — in context with other photos taken that day, some of which we are publishing for the first time.

On April 2, 1992, a young American photographer named Ron Haviv embedded with Arkan’s Tigers.

He captured on film one of the conflict’s first apparent war crimes. Over two days, the Tigers and other allied combatants killed at least 48 people, many of them execution-style, according to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

A story about Haviv's photo ran in American Photo Magazine in 1993.

The Wikipedia entry titled “Bijeljina massacre” features Haviv's famous photo, as seen in 2022.

The photo spread widely as a defining image of the conflict.

An article from Balkan Insight (Balkan Investigative Reporting Network) in 2017 features Haviv's raised boot photo.

Coverage in Danas about Haviv being interviewed by Serbian war-crimes prosecutors in 2020.

Haviv's photo atop his 2015 opinion piece in The Washington Post.

Haviv's photo as it was first published in Time Magazine in 1992.

A depiction by artist Uğur Gallenkuş on Instagram in 2021 of Haviv's iconic photo contrasted with a soccer player kicking.

In Bosnia, Dženita Mulabdić keeps this page torn from a German magazine that she first saw in a doctor's office in the early 1990s. Photograph of page by Jorgen Samso/USC Shoah Foundation

In 1993, a year or so after fleeing Bijeljina, Dženita was sitting in the lobby of a doctor’s office in Germany, paging through a magazine to pass time.

She was a refugee, a single mother in a country that was not her own. She wanted to go home.

As Dženita flipped the pages, she stopped at a one in black and white. There, blown up to fit the page, was the photo of the young commando swinging his boot towards her mother-in-law, Tifa.

Someone had combined Haviv’s photo with another black and white picture, of a soccer player kicking a ball next to the bodies of Tifa, Abdurahman and Hamijeta Pajaziti.

There was no photo caption, no photographer credit, no context.

Dženita ripped the page out and stuffed it in her purse. She was “shocked,” she says.

Arkan during a 1992 interview on Roger Cook Reports, pointing at photographs Haviv took in Bijeljina.

Disinformation has swirled for years around the image, some of it initiated by Arkan himself.

“The photographer which made this picture, he is a friend of mine,” Arkan told British journalist Roger Cook in October 1992.

“This lady was shot by the Muslim sniper,” Arkan said, adding that the man pictured mid-boot-swing was simply trying to see if she was alive, using his foot.

Josh Lee/USC Shoah Foundation

Others have disputed the authenticity of Haviv’s photograph.

Deniers have claimed, without evidence, it was edited in Photoshop or taken out of context. In the ensuing decades, people have misappropriated it to depict other conflicts.

For instance, in 2014, certified IFCN fact checkers noted the image went viral as a blogger falsely claimed that it showed ethnic cleansing in Crimea, Ukraine.

A Twitter post from 2021 implies that Adobe Photoshop could have been used on Haviv's work in Bijeljina.

Today, online posts continue to question the photograph’s veracity.

Meanwhile, elected officials and citizens in the region are openly glorifying war criminals and denying that the Bosnian genocide happened.

Arkan’s Tigers, infamous for their brutality in Bosnia, have not been held to account for their role in alleged war crimes, survivors and experts say.

No matter how powerful and disturbing Haviv’s photo is, a single photo rarely leads to accountability.

But this photograph is not alone.

Josh Lee/USC Shoah Foundation

Members of Arkan's Tigers in Bijeljina on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

Members of Arkan's Tigers pose for a photograph in a looted mosque in Bijeljina on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

Haviv took several rolls of film in Bijeljina, including photos documenting the moments before and after civilians were gunned down.

Hamijeta Pajaziti tries to save her husband, Abdirami, after he suffered a fatal gunshot wound on April 2, 1992, in Bijeljina. Moments later, she was gunned down, too. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

He hopes his photographs and eyewitness account will lead to accountability.

A member of Arkan's Tigers swings his boot toward the body of a civilian woman, Tifa Šabanović, in Bijeljina on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

Civilians lie on the ground after they were gunned down in Bijeljina, on April 2, 1992. An armed member of Arkan's Tigers walks behind them. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

Hajrush Ziberi begs for his life as members of Arkan's Tigers detain him. He was later found dead. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

Blood stains from civilians gunned down in Bijeljina on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

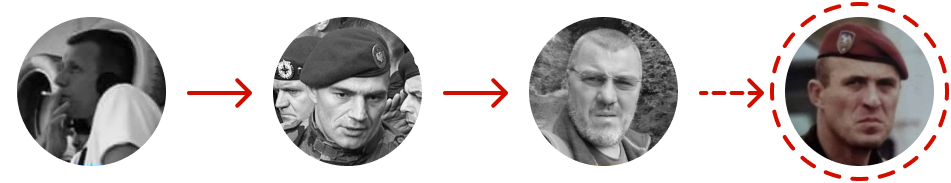

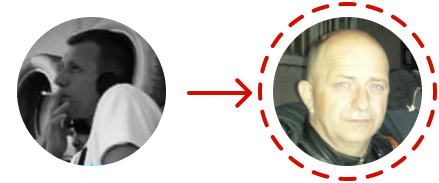

Several of the other photographs appear to show the same man, a member of Arkan’s Tigers.

The photos have unique identifying elements linking them to Haviv’s iconic photo of the soldier with the raised boot. Many have not been published until now.

They seem to point to single person: Srđan Golubović.

He resides in Belgrade, where he has worked as a DJ for decades.

Original image

A member of Arkan's Tigers swings his boot towards the body of a civilian woman, Tifa Šabanović, in Bijeljina on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

Newly published

A member of Arkan's Tigers, who appears similar to more recent photos taken of Srđan Golubović, is pictured on a motorcycle in Bijeljina, on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

Members of Arkan's Tigers in Bijeljina on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

A member of Arkan's Tigers, who appears similar to more recent photos taken of Srđan Golubović, leans over a hospital bed in Bijeljina on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

A member of Arkan's Tigers, who appears similar to more recent photos taken of Srđan Golubović, speaks to a nurse and a woman at a hospital in Bijeljina on April 2, 1992. Ron Haviv/VII/Redux

To authenticate and preserve these images, Rolling Stone teamed up with the Starling Lab.

They digitized Haviv's slides, developed from the very 35mm film in his camera in Bijeljina decades ago.

Using Starling Lab’s custom-built system, Haviv helped scan the photographs.

Each file was immediately sealed with advanced cryptography to establish that the “authentic” digital pixels came from the scanner we used and were not edited or visually altered.

As each original photo was saved by the scanner, Starling Lab ran it through a math formula that generates a unique ID number, called a “hash” and locked it with an encrypted key.

Think of the result as a digital fingerprint, created and sealed by cryptography.

If someone were to change even a single pixel of Haviv's photos, running the altered image through the same formula couldn't generate a matching fingerprint — which would help expose the fake.

Working with genocide scholars at the USC Shoah Foundation and engineers at Stanford University, the signed digital hashes were registered on three tamper-proof ledgers.

We then preserved all the files in a first-of-its-kind archive on the decentralized web.

Tens of thousands of servers now hold immutable records of the authenticity of Haviv’s files.

This ensures the archive is more resilient and can withstand the test of time.

You can see the hash in an “Authentication Certificate” made for each document in the archive by clicking the circled icon on the image.

In each certificate you can explore over 10 different cryptographic methods used in the archival process.

Go behind the scenes as the technology is deployed.

Haviv’s photographs captured Arkan’s Tigers in action in Bijeljina.

But many questions remain, including: Who bankrolled the infamous unit? A set of classified Serbian State Security Service payroll logs from 1994 and 1995, obtained by Rolling Stone, suggests some answers.

the network